The Greenpoint Neighborhood in Brooklyn, How Teresa Chmura and Brian McMahon Assembled Their Clifford Place Collection, and Minnesota Connections

Most of the artists relocated to Manhattan, but several found refuge in the predominately Polish neighborhood of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, joining the emerging arts cluster already forming. Greenpoint was a safe and reassuring environment for immigrants. The Polish language dominated conversations at restaurants, bars, coffeeshops, bookstores, banks, national chain drug stores, churches, and throughout this vibrant community of 30,000 people. There were several local Polish language newspapers, and a network of community support services. Greenpoint retained its strong ethnic identity in large measure because of the constant flow of Poles back and forth between the two countries. Those who secured a travel visa to the U.S. generally came to work for a year or two with the intention of sending money back home. The gap in the economic standard of living between the United States and Poland was wide, as workers could earn at least ten times more per hour in America. There were also dramatic differences in lifestyle. Many rural Poles who arrived were unfamiliar with the typical supermarkets that Americans took for granted and had to be schooled in such modern devices as escalators, revolving doors, and in a few cases, indoor plumbing. But the immigrants brought an extraordinary energy, vitality, and a willingness to work hard. Men typically found work in the construction industry at a time when foreigners faced little discrimination and immigration rules were not stringently enforced. Undocumented workers were generally paid in cash and could be found on construction sites throughout the city – even the iconic Trump Tower project on Fifth Avenue. Polish women tended to work in retail businesses where they could learn to speak English. Older Polish women often found work on the night shift cleaning Manhattan office buildings.

Teresa Chmura was a Polish immigrant who moved to Greenpoint. She was raised in a small village in eastern Poland in a house without indoor plumbing. She found work at a clothing store on Manhattan’s famed Orchard Street even though she spoke very little English. Ironically, she was hired because she spoke Russian, a language that was required of all students in Polish schools. Through hard work and remarkable resilience, Teresa soon owned and operated a delicatessen in Greenpoint.

Brian McMahon settled in Greenpoint in 1983, where he established an architectural design-build business. They met and the following year got married. They bought a three-story row house on Clifford Place which had been gutted by fire. While making plans for its renovation, they decided to include a public art gallery for their own enjoyment and to provide a community amenity. They organized several exhibits at their FFA Gallery, featuring local artists who were able to sell their work directly to the public.

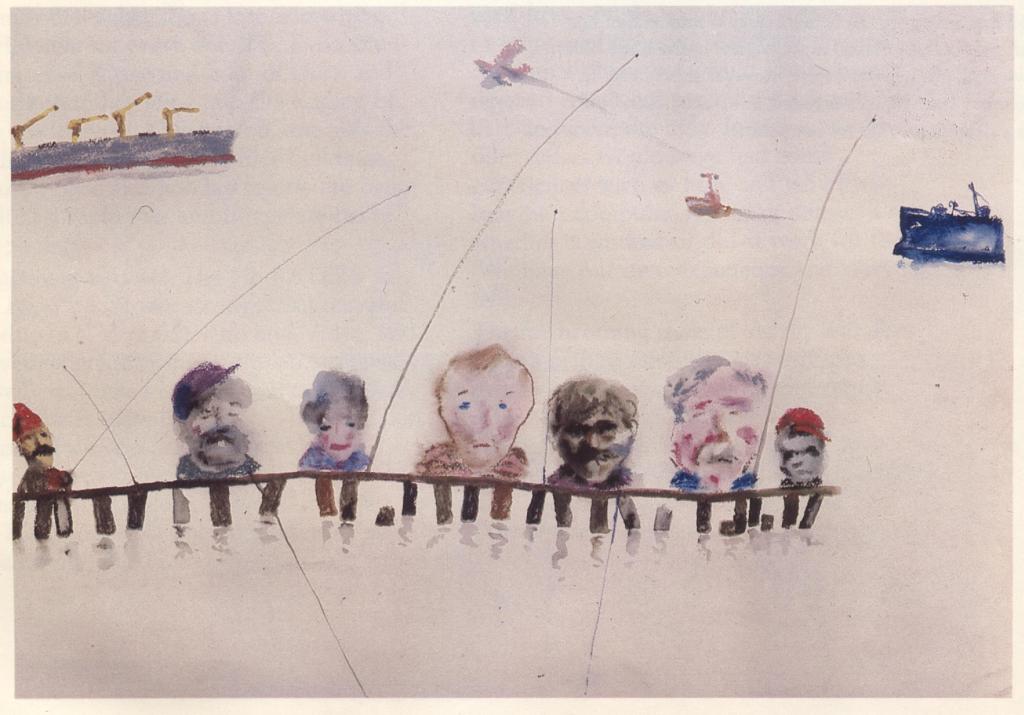

In 1986 the McMahon’ commissioned Andrzej Czeczot (1933-2012), a well-known artist in Poland, and newcomer to Greenpoint, to do a show portraying their neighborhood which was being ‘discovered’ by Manhattanites seeking less expensive housing options. Greenpoint is located on the East River directly across from midtown with spectacular views of the skyline. Czeczot beautifully captured the changing neighborhood portraying it with his characteristic wit and irony.

The exhibit, which was sponsored by the local Polish Bookstore and community bank, was well received by the New York Times and other media outlets, even reaching a major arts publication in Australia. The gallery quickly became a social hub for Polish artists in the New York area.

By the late 1980s, the McMahon’s had the extraordinary privilege of exhibiting or working with some of the most important Polish artists of that time. Wiktor Sadowski (b, 1956) spent several months with the McMahons in 1988 working on his portfolio which he lugged around on the subway calling on prospective commercial clients, often without an appointment. The New York Times upon seeing his impressive work offered Sadowski a commission on the spot to illustrate a story about families. Sadowski enlisted McMahon’s young son, Tadeusz, to serve as a model. His illustrations were published on the cover of the New York Times Magazine in January, 1989, and elsewhere throughout the article. Reportedly, the artwork elicited the most enthusiastic response the paper had ever received. This widespread exposure brought Sadowski numerous other commissions which he pursued upon his return to Poland. In 1995 he designed a poster for the Theatre de la Jeune Lune in Minneapolis for their production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

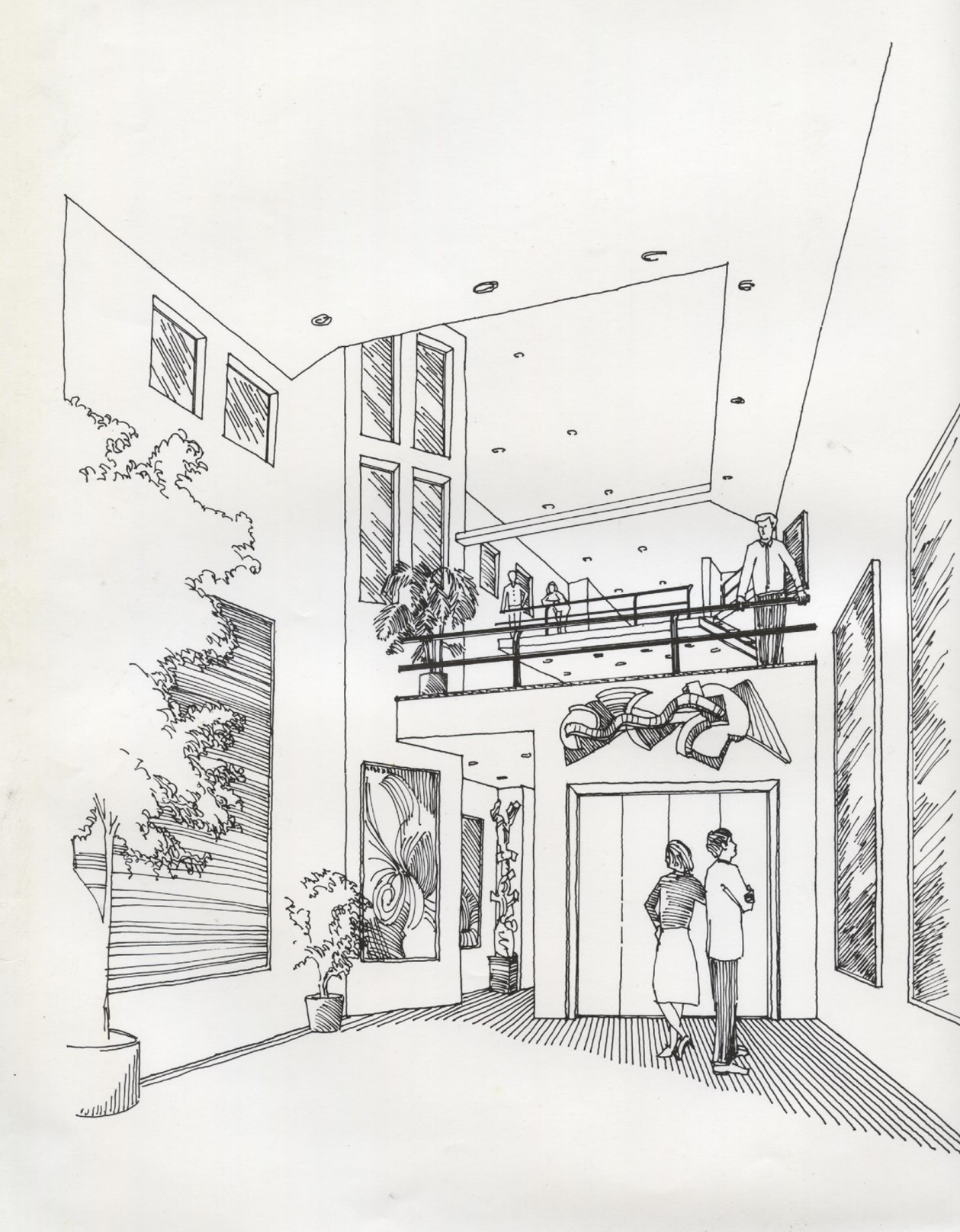

The McMahons also befriended Jan Sawka (1946-2012) who left Poland “after playing cat-and-mouse with a KGB fellow.” During his remarkable career in Europe and the United States he did more than 70 one-man shows and had his art placed in the collection of 60 museums including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre George Pompidou in Paris. He is known for the design of an important poster supporting the Solidarity movement, but he worked in virtually all media. In 1989 he designed the movable 10-story stage set for the Grateful Dead’s 25th-anniversary concert tour. Sawka worked with the McMahons developing architectural concepts for a commercial building complex in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

In addition to acquiring a number of original art works, the McMahon’s also bought over 400 Polish posters, most of which had been rolled up in storage for over thirty years. The McMahons moved to Minnesota in 1990 and were pleased to learn of a local connection to the Polish art world who arrived the same year. Piotr Szyhalski immigrated to America and found a position as a Media Arts professor at the Minneapolis College of Arts and Design. He was well versed in the tradition of poster art, which he demonstrated during the COVID pandemic. He completed a new drawing every day for 225 days, an accomplishment described as “a vivid visual digest of current “news shrapnel,” which he posted on social media. The internet had become, in effect, the new construction fence, offering some relief from those difficult times. As arts critic Shelia Regan reported, “… Szyhalski’s pandemic images went viral. Printed as posters, they were hung on street lamps and boarded up buildings in cities across the United States.” These were also shown in exhibitions at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. In 2022 the Weisman Museum of Art did a major exhibition of his art in 2022. (Pictured below.)