The Polish people were among the first to recognize the importance of the modern poster, hosting the first International Exposition of the Poster in Krakow in 1898. Poles did not achieve national sovereignty until the end of World War I, at which time artists used the poster to promote a national style that took root on the streets. The devastation of two world wars made it difficult for artists to afford, or even find, the most basic painting supplies. The poster became an important indispensable outlet for artists.

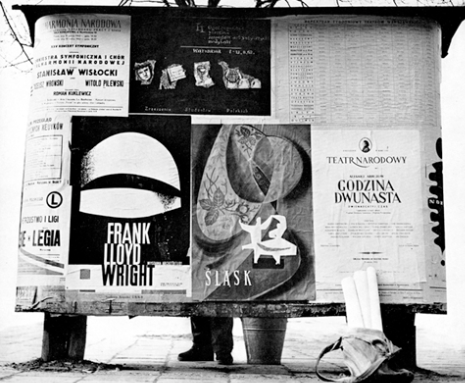

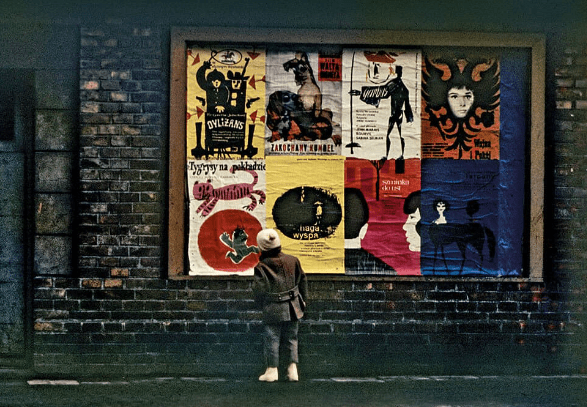

Ironically, it was the new Communist government after World War II that helped support the artists. It had nationalized all forms of artistic expression and assumed the role of patron by commissioning artists to design posters. With the communications infrastructure of the country destroyed during the war, the government recognized that posters offered an inexpensive and efficient way to reach the people. Colorful posters were plastered on construction fences all around the bombed-out country, offering some visual relief.

In addition to conveying news and political information, posters also promoted cultural events including movies, opera, and the circus. The government required foreign film companies to use Polish artists for their posters, a policy which had both economic and artistic benefits. Because artists did not have to deal directly with movie studios or manufacturers, they had considerable latitude as to how to convey advertising content. Imagination and graphic flair were deemed more important than a literal portrayal of the subject being promoted. The ephemeral nature of the poster, which was printed on inexpensive paper and left exposed to the elements, also made it easier for the artists to feel less inhibited and more experimental.

Not surprisingly, government patronage eventually turned to censorship as the communist rulers sought to rein in the artists who were subtly interjecting political messages. “It was like the Olympics,” one poster artist said,

“They wanted us to win medals… Our challenge, our game, was to win with the censors.”

The ‘game’ played by the artists was to make extensive use of metaphor, symbolism, allusion, and visual puns to slip their message past government censors. In one noted example, Jan Sawka designed a circus poster with a trapeze artist walking high above the crowd wearing a prison garb. Extensive use of symbolism had the effect of bringing more attention to the posters, as the public grew accustomed to searching for hidden meanings. The lettering of most posters was done by hand, and the text became an important visual element. The human figure generally dominates the composition, with the face often rendered in profile view. Additionally, faces are frequently masked, often shown with various layers that are manipulated visually.

During the 1960s the Polish Communist government intensified censorship and repression as the economy faltered. In 1967, the government launched an antisemitic campaign to force Jews to leave the country – and to distract from their failed economic policies. The following year, there was a massive uprising of students, artists, and workers, protesting censorship and other government policies. Repression and resistance worsened over the next decade, and in 1980 the Solidarity Movement was formed to fight for the rights of the workers. State officials were determined to quell the massive uprisings and they declared Marshall law. Artists were no longer permitted to enter international competitions, and the government even restricted the supply of paper and art supplies.

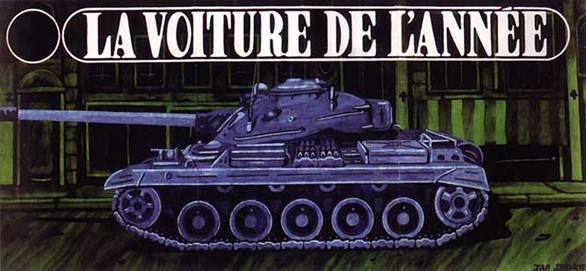

Artists strongly embraced the Solidarity Movement, and their poster messages became less subtle and more confrontational. After the imposition of martial law, Jan Sawka did a poster titled, ‘Car of the Year,’ showing a tank. Some artists were imprisoned. Many opted to relocate to New York City, where they faced an uncertain future – the art world did not necessarily value their rigorous classical training and high level of technical skill. One artist quipped, “American art is simple, abstract, rough. I sometimes feel I should move my brush from my right to my left hand, and then maybe I’d get my work in a gallery.” The one area where immigrant Poles continued to find great success was doing commercial illustrations for leading publications.

Over fifty prominent artists left for New York City, where they faced an uncertain future – the art world did not necessarily value their rigorous classical training and high level of technical skill. One Polish artist quipped,

“American art is simple, abstract, rough. I sometimes feel I should move my brush from my right to my left hand, and then maybe I’d get my work in a gallery.”